Carolyn Emerick, one of my favorite writers, penned this tremendous article and just in case like me you are in a tryptophan stupor, but still feel the need to do something constructive, please read this.

The First Thanksgiving in 1621, by JLG Ferris 1912

American Thanksgiving and the Wampanoag Tribes

Thanksgiving Fact and Fiction

Nations need myths of national identity. They give citizens an emotional tie to their country. Stories about the birth of a nation provide legitimacy to the government.This is why the Roman Empire relied on the myth of Romulus and Remus to lend credence to the city of Rome, and the Roman Empire by association.

Likewise, as long as human beings have depended on agriculture for our sustenance, we have celebrated harvest festivals. (Read about harvest fests around the world here)

It just so happens that the American national myth also happens to be a harvest festival. But, unlike the Remus and Romulas tale, ours does have some basis in fact. It is accounted for in primary documents written by Mayflower passengers (which you can read here and here).

It is actually true that the first settlers in the New World did feast with their Native American neighbors. It is not true that the British colonists were starving and desperate at this time, however. The pilgrims were fortunate to have been taken under the wing of local Natives who showed them the lay of the land and how to grow indigenous crops. We know from primary accounts that both the Natives and the settlers provided food for the first Thanksgiving feast.

This National Geographic article gives some history on Thanksgiving. However it says one thing that appears to be wrong. It says we only have one source documenting the first Thanksgiving. But this link from the Pilgrim Hall Museum lists three.

Primary documents testify that the Native guests brought venison to the feast, and the colonists brought their own vegetables and small game. The first Thanksgiving hosted approximately 50 English settlers and 90 Native Americans. (Another great source for Thanksgiving info is this paper by the Library of Congress.)

A National Holiday

The first Thanksgiving feast was not repeated for over 200 years when a letter from Edward Winslow, an original Plymouth settler, was unearthed which detailed the great feast in 1863. It was so popular at the time that President Abraham Lincoln declared it a national holiday.And, now we come full circle with the sentence above: Nations need myths of national identity. The United States was smack in the middle of Civil War when Lincoln established Thanksgiving as a national holiday. He was in the midst of fighting to hold the country together and asserting that no state has the right to secede from the nation. So, a national foundation story was badly needed just then. How convenient that the document detailing Thanksgiving was discovered right at that moment.

First Encounters

The Native Americans who held territory in the area where the English settlers landed were of the Wampanoag Nation.The fact that the Natives were welcoming and kind to the settlers in New England seems to be very well documented. However, both groups were naturally suspicious of one another.

Although the pilgrims seem to have chosen their landing point by sheer happenstance, the Plymouth Bay area had been visited and scouted in recent years before their landing. These visitors were not connected to the English pilgrims in any way. They were primarily French explorers and fur traders.

Previous visitors describe a bustling and prosperous settlement. Historians estimate that there may have been as many as 21,000 to 24,000 people living there in the years immediately before the arrival of the pilgrims. A horrific plague decimated their population.

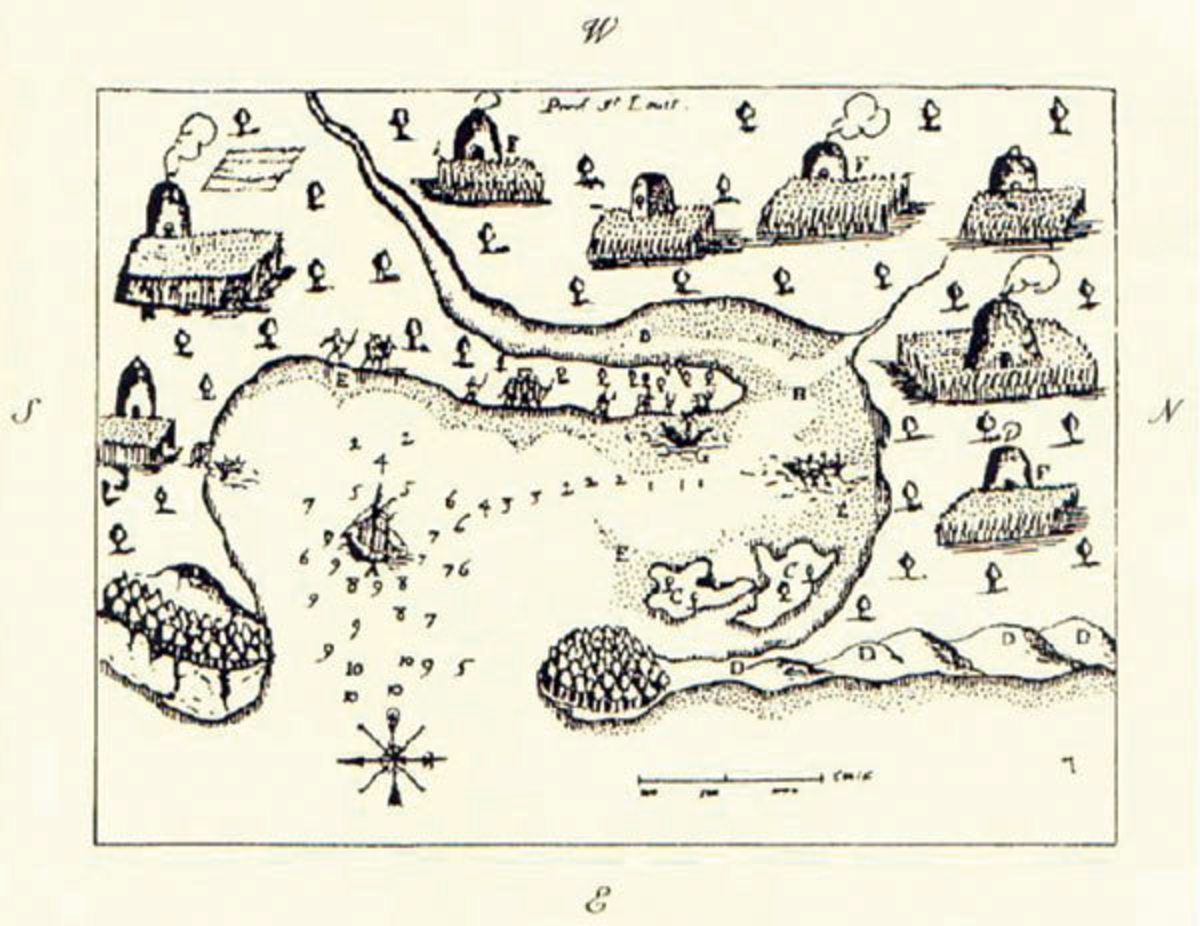

Below is a drawing of the Native American settlement at Plymouth circa 1606.

Patuxet Villiage at Plymouth Bay, Early 17th Century

Confusing Historical Events

Some other instances from history may cause the confusion in making some people think that the English settlers caused the plague among the local Natives:- The Spanish Conquistadors brought disease to the Natives in South America and the Caribbean Islands.

- And, a tale has been told of the U.S. government purposely using biological warfare to give smallpox to Native Americans later in the 1800s. But, this has been denounced as false, (see this paper from the University of Michigan).

Epidemics and Hardships

The Wampanoag were a Native American people living in the southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island area at the time of English settlement. They had been a prosperous community with a large population, but suffered an epidemic which killed off a substantial portion of the population immediately prior to the English landing at Plymouth.This is another area of confusion regarding history. Some assume that these English settlers brought disease. But the Natives in the east coast experienced an epidemic before the pilgrims landed.

That doesn't leave Europeans off the hook completely, however. It is now thought that explorers and traders who visited the region, in the years before the pilgrims landed, brought rodents carrying disease which infected the local water. This is a hypothesis, but still not a provable fact. The truth is, we don't know for sure what the plague was. But you can see this scholarly article for more information on this theory.

The real history demonstrates that while the New England settlers had a difficult first winter, the Native Americans in the region also had recently suffered rough times. So, in this particular instance, both the Europeans and the Natives were willing to help each other. If only this was the case in other epochs of American history.

Tribal Structure

There is often a conflation of terms when discussing Native American tribal organization. But here are some points to help clarify:- Tribal structure varied by region. After all, life in the northeast was very different than life in the Great Plains, and so forth.

- There tend to be three levels of societal structure in Native American society - Nation, Tribe, and Clan.

- An Indian Nation is comprised of many tribes who share language and regional ties. For example, the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Nation is made up of the Seneca, Mohawk, Tuscarora, Onondaga, Oneida, and Cayuga tribes.

- Tribes are subdivided by Clans. Clans are usually extended family groups. For this reason, many Native Clans have customs that forbid intermarriage within the same clan, to prevent inbreeding.

- For example, the Seneca tribe is divided into eight clans named for animals, such as the Wolf Clan.

- Tribes or clans not belonging to a nation were vulnerable to attack and absorption into neighboring tribes.

The Wampanoag Nation

The Wampanoag were a Native American people living in the southwestern portion of Massachusetts at the time that the English landed in Plymouth in November, 1620.They also occupied the areas now known as Rhode Island, Nantucket, and Martha's Vineyard.

Like other Native groups in the region, the Wampanoag were a nation comprised of many tribes (see the description of tribal structure to the right).

The Patuxet tribe had recently occupied the area where the English landed. They named it Plymouth Bay, but it had been known as Patuxet village to the Wampanoag.

The great plague had completely decimated the Patuxet only a few years before the pilgrims landed. It was recorded in first hand accounts that crops were found growing that must have been planted just three or four years prior.

This situation, while devastating to the Wampanoag, was a boon for the pilgrims. When they landed, they encountered a land that was brimming with abundant food sources without anyone claiming territorial rights to it.

Wampanoag Nation Territory

Squanto - the last Patuxet

There is one member of the Patuxet tribe you may already be familiar with. Tisquantum, more commonly known as Squanto, made his way into American history and legend.He had previously been captured by European merchant vessels in the New World. He was sold into slavery and ended up in Spain. Squanto was eventually given his freedom. As a free man he booked passage to England where he was able to make his way back home.

Arriving back at his former village of Patuxet, he found that it had been ravaged by disease and there were no survivors. Squanto was the last living person in his tribe.

During his time with the English he learned the language. For this reason, Squanto was introduced to the English settlers at Plymouth as a translator. Despite his time as a slave and the horrific experience of returning home to find every last family member dead, Squanto agreed to help the colonists.

Not only did he work as a translator, he also taught the New England settlers how to cultivate corn, fertilize the land, and even helped then broker peace with other nearby tribes.

Bias and Balance

For most of America's history, interactions between Europeans and Native Americans has been told through a skewed lens that favored Europeans and marginalized Natives. Today, more than ever before, it has become mainstream to take a more honest look at history and consider the viewpoints of other groups of people.However, what can sometimes happen is that the pendulum swings too far the other way. It is becoming the trend to demonize Europeans (sometimes deservedly, sometimes unfairly) while placing other groups on a pedestal that can sometimes be unrealistic.

I think it's important to tell all of history with an unbiased viewpoint that is fair to all cultures involved. Admittedly, this can be difficult to do. Especially when the other viewpoint is not well documented.

The Wampanoag Perspective

Ramona Peters is the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for Mashpee, one of the tribes within the Wampanoag Nation. In 2012 she gave an interview to the website Indian Country Today Media Network called "What Really Happened at the First Thanksgiving? The Wampanoag Side of the Tale."The interview seems to have occurred off the cuff, so she doesn't name sources for her information. However, her role as tribe historian lends credence to her opinion. And her account jives with another article from the same website which does list a primary source. The article is called "The Wampanoag Side of the First Thanksgiving Story," by Michelle Tirado.

The story described by both women, which was apparently recorded by Mayflower pilgrim Edward Winslow, is slightly different than the version that has slipped into national myth.

They say what really happened was that after such a difficult first winter, the pilgrims were celebrating a successful harvest. Where the story deviates is that in this version the settlers had not invited the Wampanoag to the party.

The Wampanoag had heard an unusual amount of gunshot going off, and came by to check it out. The gunshots were being fired off partly due to hunting for the feast, but also in reckless revelry of celebration. Being that the settlers and the Wampanoag had signed an agreement to defend one another, the Wampanoag tribe sent armed warriors to investigate the gunshot.

Due to their immense debt to the Natives for teaching them the lay of the land and protecting them from other tribes who might have been hostile to the English, the Wampanoag were welcomed and invited to stay. Since the warriors outnumbered colonists almost two to one, they sent some of their men out hunting to contribute to the feast.

Daily Gratitude

“Every day (is) a day of thanksgiving to the Wampanoag . . .(We) give thanks to the dawn of the new day, at the end of the day, to the sun, to the moon, for rain for helping crops grow. . . There (is) always something to be thankful for. .. Giving thanks comes naturally for the Wampanoag.”- Gladys Widdiss, Wampanoag tribal elder.

Native American Feelings on Thanksgiving

In the same interview, Ramona Peters goes on to explain how she, as a Native American, feels about the Thanksgiving holiday.In the days preceding Thanksgiving each year, articles flood the internet discussing the dark side of Thanksgiving. They report that to Native Americans, it is a Day of Mourning. Many of these articles are very harsh in their judgement of the English pilgrims.

Ramona Peters doesn't express a strong negative opinion in her interview, however. Yet, she does point out a few facts that she feels it is important to note:

- Traditionally, when the Thanksgiving story is told, the Wampanoag Nation goes unnamed. They are generically referred to simply as Native Americans.

- Even though the Native Americans are present in the story, the only god mentioned in the Thanksgiving story is the Christian God. The Wampanoag warriors would have given thanks in their own way. She does not go into great detail about Wampanoag spiritual beliefs here, but she does mention Mother Nature and a Creator.

- Apart from thanking Mother Nature, Ms. Peters says that the Wampanoag would have given thanks to their human mothers as well.

Gratitude in Native Spirituality

From these and other sources we learn that "thanksgiving" was a regular part of life for many Native American peoples. In the Northeast, lifestyles typically consisted of a combination of hunting, fishing, foraging, and agriculture.The cosmological outlook was very similar to the indigenous European (pagan) worldview. In societies that were tied so intricately to the Earth, spirits of the land, animals, and elements were immensely important. Offerings would be given to the Earth in gratitude for her abundance.

This creates a reciprocal relationship between humankind and the Earth. Since so much emphasis is placed upon the Earth, and gratitude is an important feature of spirituality, the notion of giving thanks occurs in tune with agricultural cycles.

In some Native American cultures, thanksgiving is offered regularly, independently of agriculture. For example, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) have a Thanksgiving Address which is recited at tribal gatherings, celebrations, or even as a daily affirmation or mantra.

© 2014 Carolyn Emerick