Words and pictures

Tuesday, February 24, 2026

Saturday, February 21, 2026

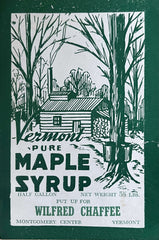

MAPLE SYRUP, sugarhouse, a snowstorm...

THIS HAS BEEN A COLD AND SNOWY WINTER, MUCH LIKE THOSE I REMEMBER FROM CHILDHOOD. ANOTHER CHILDHOOD MEMORY WAS THE SUNDAY DRIVE TO BUY MAPLE SYRUP AT A "SUGARHOUSE", THEY WEREN'T HARD TO FIND, BUT THE DRIVE ON UNTENDED BACKWOODS DIRT ROADS, COULD BE A REAL ADVENTURE. MAPLE SYRUP, REAL MAPLE SYRUP, NOT THE STUFF FROM 'THE MARKET

IS FLAVORLESS, WAS WORTH IT.

A PLATE OF FRESHLY HOMEMADE ENGLISH MUFFINS, KNOWING THAT A MAJOR SNOWFALL WAS IS FORECAST FOR TO NIGHT, WELL THAT WAS ENOUGH, OFF WE WENT TO FIND A "SUGARHOUSE". IF THERE WERE ANY STILL IN THIS AREA.

SUNSET COMES AT ALMOST 6pm NOW, A GOOD THING BECAUSE THAT IS WHEN WE SPOTTED THE BILLOWING CLOUDS OF STEAM CAME FROM A BUILDING THAT LOOKED LIKE IT WAS AN OLD TYME MOTORCYCLE GARAGE, WHICH WAS ONCE. THE SUGERER EXPLAINED THAT IT WAS FOR A VERY LONG TIME AGO, BUILT IN THE 1920'S!

FIXING IT UP AND MAKING SYRUP P WAS HIS DREAM FOR THE SMALL FARM IT WAS BUILT ON. WE BOUGHT SOME MAPLES SUGAR, AND SOME REALLY STICKY MAPLE CANDY, AND A FINE MASON JAR FILLED TO THE TOP WITH DARK MAPLE SYRUP. BY THE TIME THE SUN HAD SET AND NIGHT WAS TAKING OVER WE WERE WELL ON OUR WAY HOME, WHEN THE FIRST FLAKES BEGAN TO DRIFT DOWN.

A SNOW FLAKE HERE AND A SNOWFLAKE HERE SPARKLED IN THEN HEADLIGHTS. IT WAS GOOD TO GET HOME, GOOD TO FEEL THE WARMTH OF THE OLD COAL STOVE AND GOOD TO ENJOY A FRESH English MUFFIN, WITH FRESH MAPLE SYRUP AND SOME NEW MEMORIES.

SWEET DREAMS!

The Old Sugarhouse

The old sugarhouse still sits peacefully in the woods, its joints creaking with the wind, its wood slowly decaying as young maple trees grow up around it. The first picture was taken in the 1960's and the second picture was taken last week.

The sugarhouse was built by Harvey’s father, Wilfrid. He bought the land it sits on in 1941. The property was a very old farm with various outbuildings that were in disrepair. The sugarhouse was built shortly after Wilfrid purchased the land with lumber that was salvaged from the old buildings.

Wilfrid started out with buckets, a wood fired arch, and no electricity. He gathered the sap with two sturdy work horses that followed voice commands. Several local workers helped Wilfrid with sugaring, but two men, Richard “Keiser” Elkins & Cat Lumbra were his main help. Keiser & Cat were known as tough, hard-working men. Anyone trying to keep up with them for the day had their work cut out for them. Keiser was the person who would issue the commands to the work horses during gathering times.

Boiling was an art and a science during this time (as it still is today). The time to draw-off the perfect syrup was gauged by holding up a scoop of hot syrup and having it drip off the scoop. When the syrup was ready it would fall off the scoop in sheets just the right way. It took a lot of experience to judge this exact moment.

Wilfrid married Bea in 1945. Bea joined in helping with the maple business. Bea would cook meals for the men and help with cleaning the sap filters. The sap filters were washed in the cold brook next to the sugar house to remove any niter and then they were finished washing with an old wringer washer to complete the job. Niter is a suspension of minerals and other solids that precipitate out of the sap during the boiling process.

The family time in the sugar house was the best time. Boiling eggs and hot dogs in the sap, serving hearty hot meals after a long day gathering sap, family visiting from New York & Canada, and cousins playing hide & seek in the woods. Springtime in northern Vermont was a celebration of the end of the very long, cold winter and the promise of warm sunny days to come.

Wilfred was an early adopter of sugaring technology. In the mid 1960’s the Chaffee’s began using plastic bags for collecting sap instead of buckets. These bags were hung on the spout that was attached to the tree and were pear shaped. They had a narrow neck and bulb shaped bottom. There was a problem with these bags. When the sap would freeze in the bags you couldn’t get the sap out through the narrow neck. Latter that decade the Chaffees added tubing, electricity, a vacuum system, and an oil burning arch. In 1965 Wilfrid was honored by being named Sugar Maker of the Year. The sugarhouse was last used in the early 1970's. Today Harvey and Lisa have their house on this hallowed property.

A lot has changed in sugaring in the last 80 years since this sugarhouse was built, but a lot has stayed the same. The thrill of that first run of sap, the sweet smell of steam filling the sugarhouse, the taste of syrup fresh off the evaporator, the first daffodil sprouts poking their heads through the spring snow, and finally the sound of spring peepers in the pond, signaling the end of sugaring is getting near. Sugaring still connects us with the rhythm of the seasons. We think Wilfrid and Bea would be proud knowing we at Barred Woods are carrying on the sugaring tradition.

Monday, February 16, 2026

A few words about Grandma's Kitchen and a recipe from shop class

One day I asked AI to make an image of my grandparents house, as i have none. My readers night have noted these are the images that are part of my last years Thanksgiving post. While not exactly like the house or the kitchen, they are strikingly close. So my idea was made to use them in posts for recipes. And some recipes will be new-er like this one which a friend's son brought home from shop class, shop class???

Friday, February 13, 2026

Tuesday, February 10, 2026

how many faces do you see????

This is one of those photos one usually deletes, it does not show the image i was trying to capture of large, seriously large, icicles on the side of a road-cut. That happens when one presses the shutter button on an cheap,old, digital camera while riding in a car that is traveling at 55mph, in a rainstorm and AFTER seeing the giant icicles.

But...big but....when i was previewing the images i got, deciding which ones stay and which ones go, a voice over my shoulder remarked, "how many faces are in the picture?" "Faces? what?" So, i looked and it didn't take much to find a large Aztec warrior, in the center of the photo. after that i needed a guide, and my guide found 3 more. Poor me i found no more.

Pareidolia is a phenomenon wherein people perceive likenesses on random images—such as faces, animals, or objects on clouds and rock formations.

Try as i might, I have never been very good at seeing those faces or spotting those shapes everyone else sees. Pareidolia is believed to be a survival skill our early ancestors developed.

.

Saturday, February 7, 2026

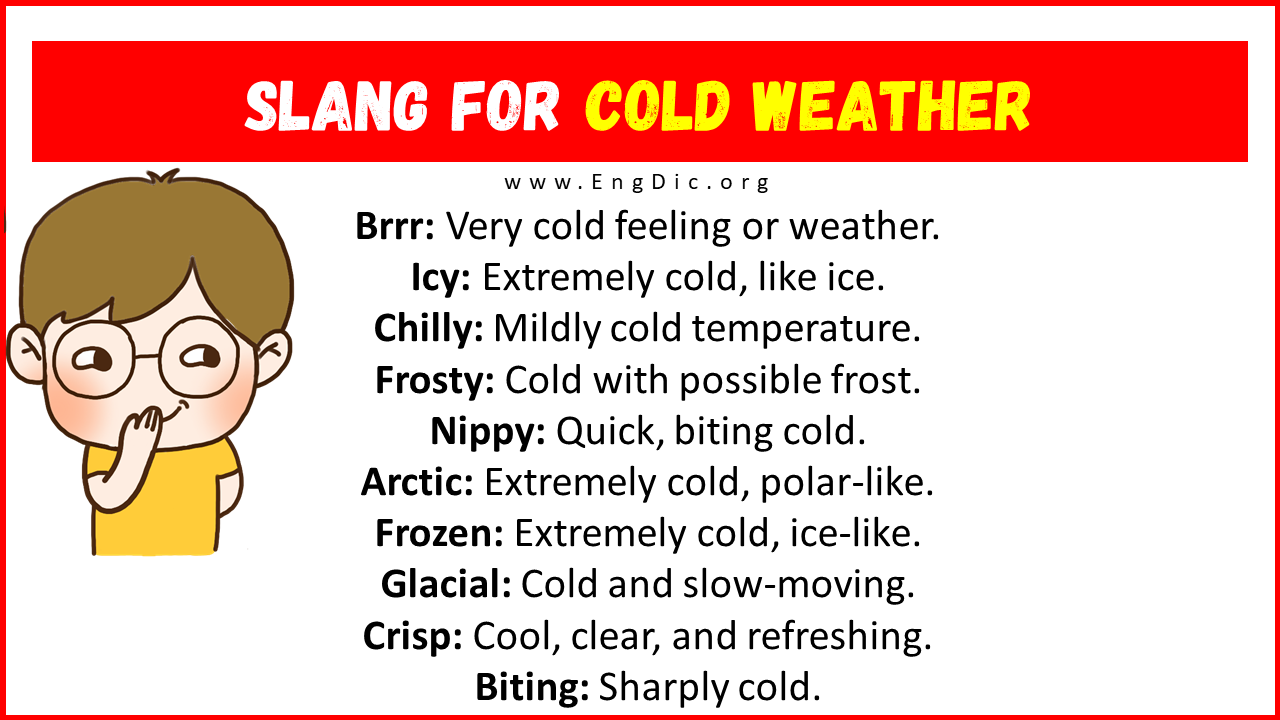

Some cold Weather words

The bluest skys, a stiff breeze and bitter cold!!!! here in the piney wood. Think i will stay indoors today. The apple cores orange peels, potato skins, onion skins, egg shells tea bags, what have you, can get a bit more pungent before they go to the compost pile......i'm NOT going out there today! It was surprising to see that last night's winds, swept the snows into a smooth even surface, looks like it could be an Arctic scene, gone where the trails of human and deer tracks that made the yard look like an all white quilt in the making, when i looked out the window. There is also a dark rectangular object that looks very much like a door, hmmm all of ours are present and accounted for. The winds are vigorously sweeping across the the yard and slowly burying it. I will be more than grateful for the warmer temperatures predicted for the coming week.

Meanwhile it will leisurely read thru my seed catalog and find the perfect variety of pumpkins to grow this year.

What does Cold weather mean? (Meaning & Origin)

Cold weather refers to conditions where the temperature is low, often causing discomfort or requiring protective clothing. The term “cold” originates from Old English “cald,” describing a lack of heat or warmth.

Slang Words for Cold weather

- Brrr: Very cold feeling or weather.

- Icy: Extremely cold, like ice.

- Chilly: Mildly cold temperature.

- Frosty: Cold with possible frost.

- Nippy: Quick, biting cold.

- Arctic: Extremely cold, polar-like.

- Frozen: Extremely cold, ice-like.

- Glacial: Cold and slow-moving.

- Crisp: Cool, clear, and refreshing.

- Biting: Sharply cold.

- Blustery: Cold with strong winds.

- Parka: Extremely cold weather.

- Sub-zero: Below freezing point.

- Wintery: Typical of winter coldness.

- Brisk: Cold but invigorating.

- Snowed: Covered or overwhelmed with cold.

- Coolish: Slightly cold.

- Frigid: Intensely cold.

- Baltic: Very cold, especially in UK slang.

- Icebox: Extremely cold space.

Use of Cold Weather Slang in Example Sentences

- It’s so brrr outside, grab your coat!

- The lake looks completely icy today.

- This morning feels particularly chilly.

- The window has a frosty layer on it.

- The wind is especially nippy today.

- It feels almost arctic outside!

- The ground seems absolutely frozen.

- His response was rather glacial.

- The air is so crisp and refreshing.

- This biting cold cuts through everything.

- It’s a blustery day, so bundle up!

- You’ll need a parka for this weather.

- With these sub-zero temperatures, stay indoors.

- The roads look very wintery now.

- I love a brisk morning jog.

- I feel snowed under with this cold.

- It’s a bit coolish, isn’t it?

- The night was utterly frigid.

- Feels rather baltic out, doesn’t it?

- This room’s an absolute icebox.

Wednesday, February 4, 2026

Here's to the people who drive the snowplows

I do thank you, all of you!

Even when you drive past my house for the umpteenth time that night, the rattle of anti skid hitting the road,the sound of the plows' blade as it scrapes away the snow and sleet on the roadway as you pass by often wake me. The lights pierce the dark and light up my room lets me know that you are out on that road making it safer. When it wakes me up enough that i get up and look out the window {sometime i'm fast enough to see the plow truck}. I love to see the flashing lights and to wave and say "Thanks for keeping us safer! You be safe out there". I even say that when your lights can just barely be seen.

Thanks!!! thank you so much.